Cancer Wars

With the help of the university’s own version of the Death Star, students in John Schmitt’s lab conduct research that could save lives

Mission is important to biology professor John Schmitt. He reiterates it in class, on the university’s website, and in interviews. His students easily recite it: “To better understand God’s creation and ourselves …”

But in the 500-square-foot Schmitt Lab, the focus is on something tearing at the fabric of creation with devastating impact, destroying God’s creatures one person at a time.

Schmitt’s goal, of course, is to stop that destroyer. This is the second part of his mission: “... and to make discoveries that advance biology and improve human health.” Ironically, something called the Death Star is integral to that mission.

“John likes Star Wars, so he calls it the Death Star,” says biology major Sophie Denham as she works with the $50,000 molecular imaging system in the Schmitt Lab. “I’m not exactly sure if there’s any more reason to it than that.”

But Schmitt’s eyebrows rise at the question. The reason for the moniker is obvious: “It makes a super cool sound as a chamber inside opens and closes, and uses lasers to illuminate the molecules,” he says. While the Star Wars Death Star vaporizes planets in the galaxy, Schmitt’s Death Star cracks open a single cell to understand what’s happening inside.

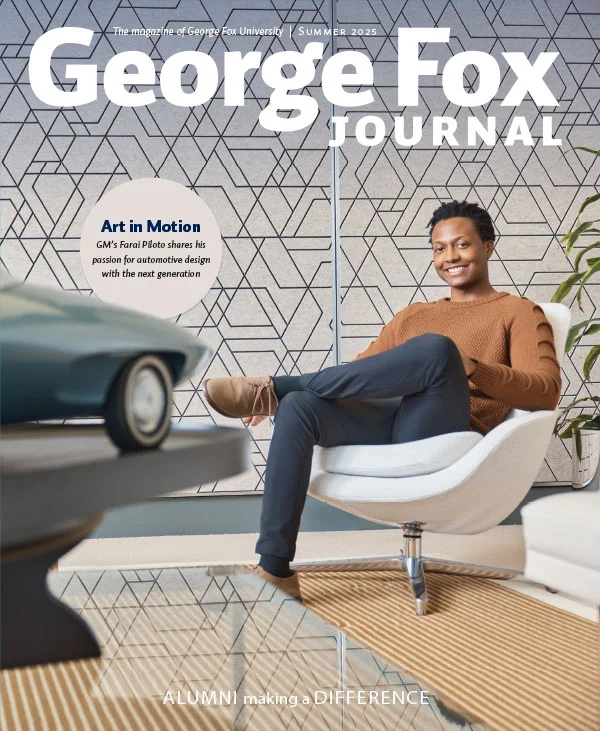

Professor John Schmitt loads a sample containing proteins into a LI-COR molecular imaging system nicknamed the “Death Star.”

Battle at the Cellular Level

Last summer, students Hannah Tranby, Jessie Bailey and Denham fed and multiplied cancer cells, probed membranes, analyzed proteins and experimented on killing what they grew – to put it in layman’s terms.

Bailey, a biology and biochemistry major, has a personal tie to cancer, but not in a way you might expect. She had asymptomatic appendicitis as a child, and after her appendix ruptured, her body went septic. Following surgery, she recovered in the surgical pediatric oncology wing of the hospital, surrounded by kids battling cancer.

“Being there with other kids, knowing that I was going to leave and they might not, that really started my interest in cancer,” Bailey says. “It was hard for me to reconcile with the fact that these kids I was playing with in the recovery rooms were potentially never going to leave that hospital – and I was only there for a week.”

Initially, Bailey viewed the summer job in Schmitt’s lab as a stepping stone to a medical degree.

“When I was thinking of going into the medical field, I thought I wanted to do pediatric oncology, and research just seemed like a great segue,” she says. “Then I realized this is actually my passion. I eventually want to teach as well, but there’s so much knowledge left to be gained and I’m fascinated by the way cancer works.”

While Bailey worked on an experimental method called the Western Blot, a technique commonly used in cellular and molecular labs to detect specific proteins, Denham, a biology major, probed membranes – a crucial step involving proteins and the Death Star.

“All the proteins we collect end up on a membrane that is analyzed in this Death Star,” she says. “It uses lasers that illuminate the proteins from cells to show us what proteins are present.”

The student researchers then add compounds like estrogen or inhibitors to cancer cells and observe as the Death Star reveals how the proteins change as a result of the cell treatments. Bottom line: The Death Star helps researchers determine what might successfully alter, and hopefully kill, the cancer cells.

Though Denham plans on medical school, a summer of research is helpful. “Research is what the medical field bases treatments on,” she says. “So even though I’m not going into research specifically, I can still appreciate the work, because I have this opportunity to see how they do it.”

While deciding between the PhD or medical school route, Tranby, a biochemistry major, used last summer to exercise a personal vendetta against cancer; her great aunt recently died of leukemia, after having breast cancer.

“When I heard that my aunt died – it was while I was doing research here – it just made me want to work even harder in the lab and try to do as many experiments as possible over the summer, just to learn as much as we can about it,” Tranby says. “It’s really frustrating when you don’t get results, but it puts into perspective that everything we’re doing here is helping the research. We understand the cell better, and that can help so many people across the world.”

Student researcher Hannah Tranby cultures human cancer cells.

Professional Careers Start Here

Schmitt has mentored more than 30 students in his lab the past 20 years, with a number of them applying to work a second year. Together, they explore the causes and behavior of breast, prostate and bone cancers, giving these 20- to 22-year-olds the opportunity to interact in the global scientific community by submitting their work to further decades-long research in an ongoing war. To date, more than 15 students have coauthored papers with Schmitt for scientific publications.

“The kind of hands-on research they are able to do is unique for undergraduates, as it requires problem-solving and technical skills that are associated with graduate-level students,” Schmitt says.

Several interns have continued in the medical and research fields. Luke Fletcher, MD (’09) went on to USC and is an oncologist. Renee Geck, PhD (’14) graduated from Harvard and teaches at Gonzaga. Others have gone to medical school at Oregon Health & Science University, Loma Linda University, Duke University and Tulane University, with careers in pediatrics, family and internal medicine, anesthesia, nursing and emergency medicine.

“Students at George Fox, in particular in the sciences, are in a position to really do cutting-edge research. The kinds of questions they’re asking ... go way beyond the scope of your traditional undergraduate teaching lab.”

“Students at George Fox, in particular in the sciences, are in a position to really do cutting-edge research,” Schmitt says. “At a large university, it might be difficult for an undergraduate to have a good hands-on project where they get to make some of the decisions, help plan out their experiments, evaluate their results, and present that information in a professional way. The kinds of questions they’re asking, the kinds of hypotheses they’re pursuing, are complicated, fascinating, and go way beyond the scope of your traditional undergraduate teaching lab.”

Bailey, Tranby and Denham had a summer of exacting, repetitive work that holds the promise of discovery. A summer of identifying options – for cancer treatment and for their futures. A summer of working individually and as a team. All three presented their research at various symposia this past year. Bailey was given a top poster award at the Murdock Research Conference last fall for her project and presentation.

One year later, Bailey is working with youth and women through a missions organization in Sierra Leone, after graduating a semester early. Denham, now a senior, is working in the Schmitt Lab again this summer, and plans to apply to medical school next spring.

Tranby, who graduated in May, also decided medical school is her next step, but a summer of research added a depth to her future that was unexpected. “Research and medicine go hand-in-hand in a lot of ways,” she says. “I think it’s really cool that the research we do leads to medical treatments and patients are able to live because of it.”

Looking for more?

Browse this issue of the George Fox Journal to read more of the stories of George Fox University, Oregon's premier Christian university.