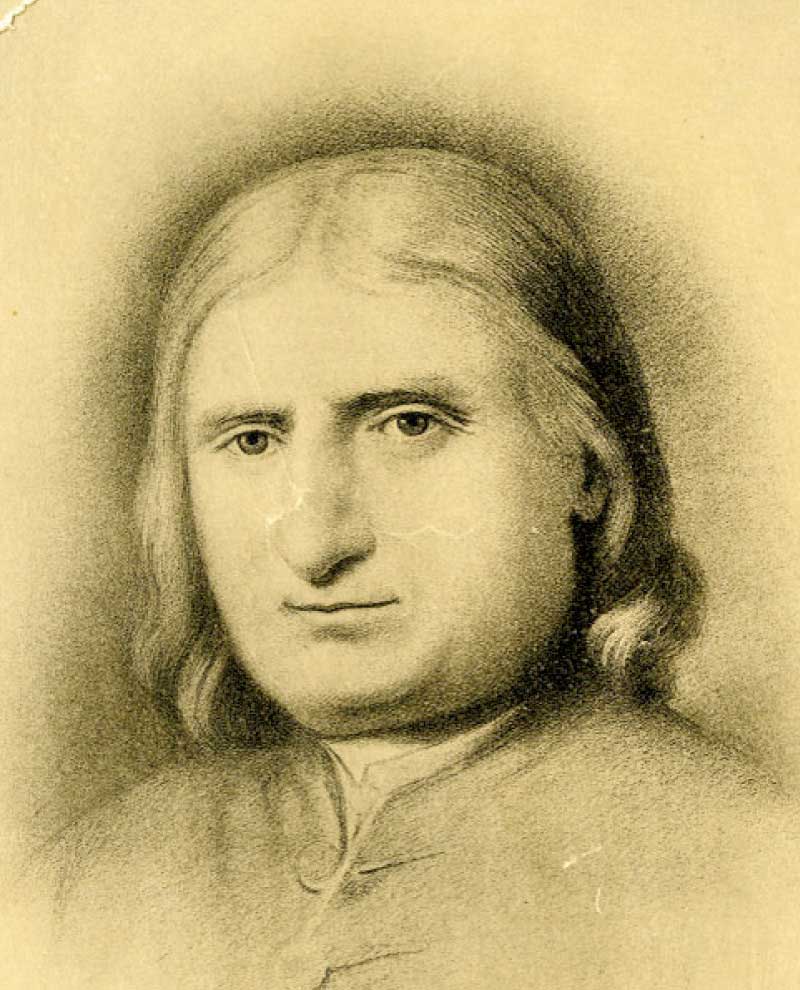

George Fox and the Quaker (Friends) Movement

"There is one, even Christ Jesus, that can speak to thy condition." This discovery of Christ as a present reality turned George Fox from frustrated seeker to joyous finder and initiated a major Christian awakening in England.

In 1647, as a 23-year-old, Fox was already a discerning critic of his culture. When human counselors could not fill his spiritual void, he turned to Bible reading and prayer, often in the sanctuary of "hollow trees and lonesome places." On some of these occasions he received "openings," e.g., that attending a university does not make a minister, that "the people, not the steeple, is the church," and that the same Spirit who inspired the Scriptures is their true interpreter.

Even as a child Fox was unusually sensitive to God, having been well taught by godly parents. He remembered experiencing the "pureness" of divine presence at the age of 11. This vision of the world as God wants it contrasted starkly with the world of political violence and ecclesiastical hypocrisy that he experienced as a youth.

Fox worked first as a cobbler and then as a partner with a wool and cattle dealer. His integrity brought him commercial success. But the spiritual conflict raged furiously within him until his experience of Christ brought peace.

A Movement Begins

From his spiritual epiphany until 1652, Fox engaged in itinerant ministry, preaching at the close of Puritan meetings, or outdoors before crowds. He exhorted seekers to heed the voice of Christ within, to be honest in business, compassionate to the needy, and to share in the free ministry of the true church. Large numbers of people were "convinced" (converted) through his preaching, and opposition intensified.

Fox was thrown down church steps, beaten with sticks and once with a brass-bound Bible! He refused to be intimidated, and his courage and physical stamina gave credibility to a central theme of his preaching: the power through Christ to live a holy life. For such preaching, Fox spent six months in Derby jail. Offered release if he would accept a commission in Cromwell's army, Fox refused, saying Christ had brought him into the "covenant of peace." For this he was jailed another six months.

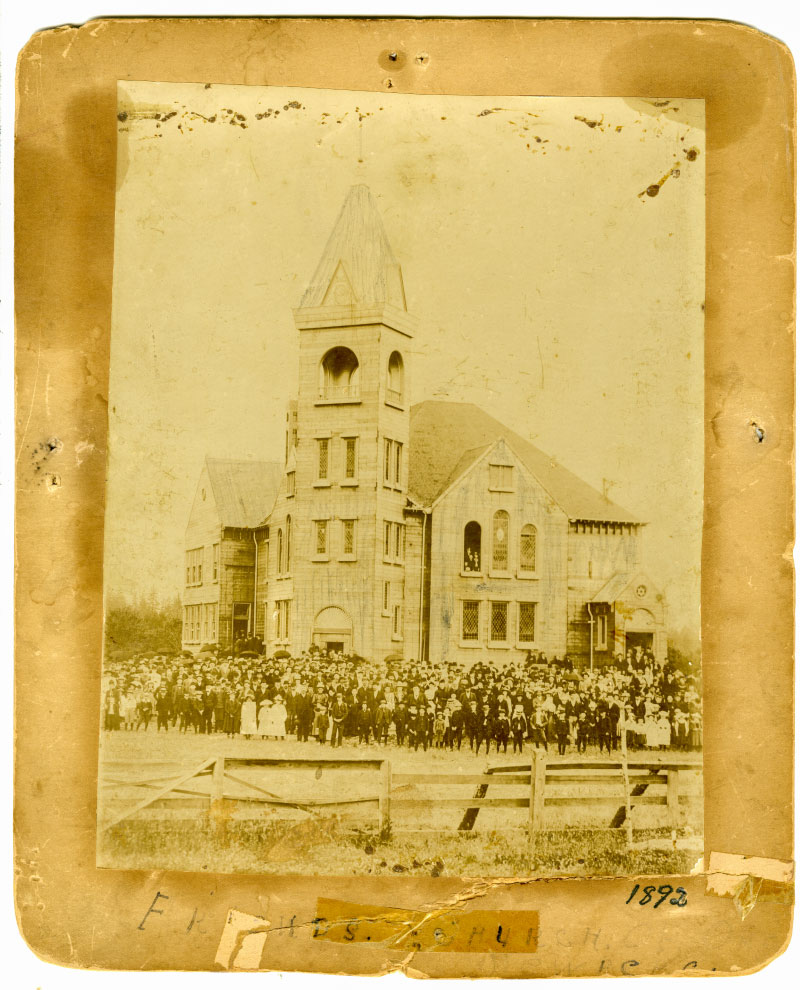

Historians mark 1652 as the beginning of the Quaker movement. One day Fox climbed up desolate Pendle Hill (believed to be a haunt of demons) and saw "a people in white raiment, coming to the Lord." The vision signified that proclaiming Christ's power over sin would gather people to the kingdom. And it did. By 1660, there were 50,000 followers.

Zealous young men and women ("the valiant 60") joined Fox in preaching at fairs, marketplaces, in the fields, in the jails, in the courts, and through the printing press. Gervase Benson, Edward Burrough, John Audland, Mary Fisher, Francis Howgill, William Dewsbury and others joined in ministry. Some men left Cromwell's army to join what James Nayler termed "the Lamb's war."

Growth and Persecution

At first these fired-up Christians called themselves "children of the Light," "publishers of Truth," or "the camp of the Lord." Gradually they came to prefer the term "Friends," in accord with Jesus' words found in John 15:14. Critics, seeing only emotional exuberance, had dubbed them "Quakers," in response to which Fox, with more fire than tact, told a tormenting judge he should tremble at the word of the Lord!

The restoration of the monarchy did not bring relief from harassment, as Quakers had hoped. In fact, the Clarendon Code of 1662 and 1664 put thousands of Quakers in prison for illegal assembly and refusing test oaths. Three were hanged in Boston for their witness to religious liberty, one a grandmother, Mary Dyer, whose statue on Boston Common testifies to the price paid for religious freedom.

After release from prison in 1666, Fox visited British Friends to set up a system of local and regional meetings, which diffused authority in what Fox believed was the gospel order. In this way, the cult of personality was resisted.

In 1669, Fox married a widow, Margaret Fell. Her home in Swarthmoor had served for many years as a headquarters, and her own public ministry (including long imprisonment) added strength to Friends. Their marriage was a loving one, and her children honored Fox and cared for him in London during his later years.

During the 1670s, Fox traveled extensively in Europe, the West Indies, and America, and sustained the movement through widely circulated pastoral letters and doctrinal writings. At his death in 1691, Friends numbered 100,000, mostly in England, Scotland, and the American Colonies.

Legacy

George Fox's personal dynamism, Spirit anointed, made him a powerful preacher, a penetrating seer, a gentle pastor, and occasionally a healer. He led into ministry servants such as Mary Fisher and aristocrats such as William Penn and Isaac Penington.

Fox could be devastating to critics, but also persuasive, as when he pled with a burdened, tearful Oliver Cromwell, "lay your crown at Jesus' feet!" To those who longed for a more authentic Christianity, Fox's sermons, rich in biblical metaphor and common speech, brought hope in a dark time.

His oft reprinted Journal is a Christian classic, and aphorisms from his letters continue to inspire, e.g., "Truth can live in the jails," "be valiant for Truth upon the earth and tread upon deceit," and "keep on the mountain of holiness." Schools in several countries bear his name, as does this one, George Fox University.